Trying to close the gap between prompting and programming

Reflections on a year of Prolog and LLMs

I began my side project, DeepClause, in late 2024, driven by a profound dissatisfaction with the state of LLM-powered applications. Whether building basic RAG-type Q&A systems, chatbots, or agents—and regardless of the tech they were combined with, from vector databases to ever-changing, unstable frameworks—the end results never felt truly satisfying.

An initial burst of excitement was consistently followed by disappointment. The systems I built would falter when confronted with slightly out-of-distribution input, triggering strange and unanticipated downstream behaviors. Minor variations in a user’s query could lead to wildly different results in a text-to-SQL engine. A summarization prompt that worked well on one document would fail miserably on another, sometimes inexplicably switching to a different language or, as one product manager memorably asked, making it seem as if “the AI was on drugs.”

As some had proclaimed 2025 to be the “year of agents”, most experiments shifted from relatively static orchestration of LLM calls to “agents”, i.e. loops around LLM calls that trigger tools. The usual pattern emerged again: initial excitement, followed by disappointment: Messed up tool calls, infinite loops, huge context with token costs quickly getting out of hand.

While the (by now) more “traditional” approach of building more or less fixed sequential or DAG-like orchestrations usually led to more predictable results, they required massive amounts of debugging, tuning, evaluations. And once built, they did not feel like the promised AI future, but more like traditional programming, just with LLMs in the loop. Agents, on the other hand, felt more like the promised AI future, but were hard to control, hard to debug, and often unreliable.

Like many others I initially overestimated (and by now probably underestimate) the capabilities of LLMs. Working with these strange objects was a far cry from Andrei Karpathy’s statement: “English is the hottest new programming language”. Yet, most non-technical people I worked with somehow acted as if prompting was indeed equal to programming natural language and trying to explain the fundamental limitations of sampling from billion parameter statistical models trained on the entire internet was usually met with a mixture of blank stares and disbelief. Nevertheless I felt that I had stumbled upon an interesting challenge: How could we actually create truly programmable AI systems on top of LLMs?

Thinking a bit about this question it seemed apt to start revisting both old and new ideas, with the ultimate hope of finding some clever way to combine these into something that could help with the whole LLM development experience. From all the new ideas, what felt the most natural to me was to use a code generation approach a la “Chain of Code” or “CodeAct”. Take a task, turn it into code, run the code. As the to the nature of the generated code itself I decided to go back to the good old days of logic programming and Prolog, since I had always felt that Prolog’s declarative nature, its meta-programmability, and its close relationship to formal logic made it a good fit for building more robust systems. Also, I just seem to have a weird obsession with Prolog ever since I first read about it...

Moreover, there seemed to be something in the air: I wasn’t the only one working on the combination of Prolog with LLMs. A number of research articles, blogs etc. were all trying to find novel ways of combining the old (Prolog/GOFAI/Planners/PDDL...) with the new (LLMs) (Some references are listed at the end). I found Erik Meijer’s work on Universalis to be particularly inspiring and hence started on a journey of late night coding sessions [3,4].

The initial idea then became to build a system where user tasks would be turned into some sort of Prolog code, but with the extra benefit of allowing predicates that would be interpreted by an LLM, leading to a kind of expert systems with “soft rules”. The hope was that this would simplify the generated code and allow the whole system to react more flexibly to user requests, while still retaining some sort of predictability and controllability through the logic programming paradigm. Moreover, one would get symbolic reasoning (in the Prolog sense), knowledge graphs, constraint logic programming and similar features supported right out of the box.

The result of this exploration is DeepClause. At its core, it consists of two components: a domain-specific language built on top of Prolog (the DeepClause Metalanguage, or “DML”) and a runtime engine that includes a meta-interpreter written in SWI-Prolog. (For those interested, I highly recommend exploring Markus Triska’s fantastic work in this field [2]). The meta-interpreter allows DeepClause to track the entire execution process, providing a detailed audit trail for free, while also maintaining global state—such as session IDs, conversational memory, and input parameters—throughout the execution. This approach also makes it easy to experiment with new language features and even modify the execution model itself. To get a taste for the DML language and its features please take a look at the appendix.

DeepClause approaches the “programmable AI” problem as follows:

Write a “structured” prompt in plain english that may reference tools, introduce variables, or define alternative ways of doing things.

“Compile” the structured prompt into a Prolog/DML using an agent, then verify/test/execute the program or source prompt as needed.

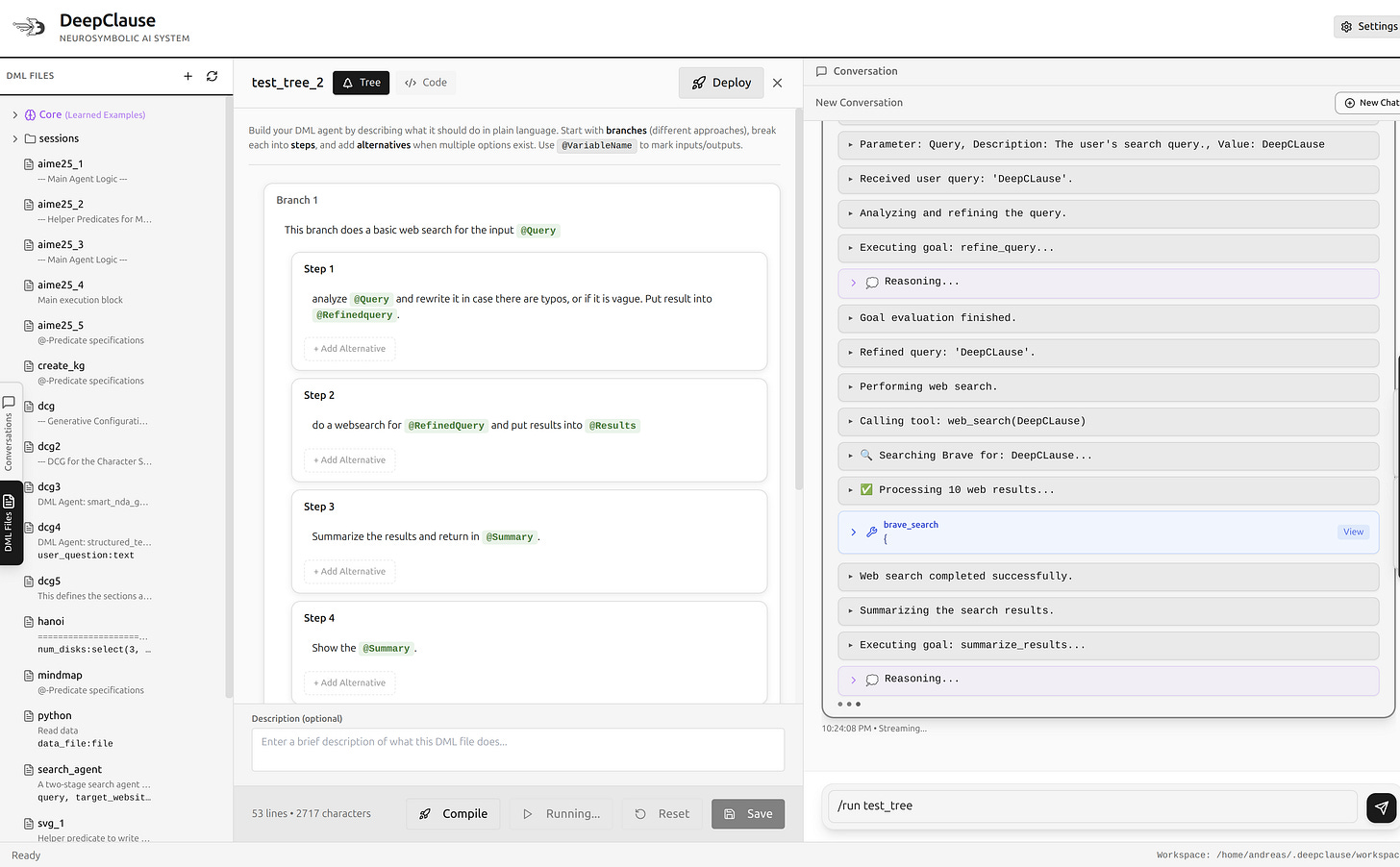

In the current DeepClause Electron prototype this looks like this:

Since we use an LLM to “compile” the prompt into DML code, we could in principle pass in any text and (most likely) get a valid DML program as output. Yet, if - by way of the UI - we force the prompt to roughly adhere to the structure and semantics of a Prolog program, the more likely we are to properly capture the prompt’s intent in code. Once a structured prompt has been turned into DML code, we can then go into a compile-check-execute cycle until we are happy with the results.

Of course, writing the structured Prompt already requires one to have a very clear idea on what the final result should look like, so I think it will make sense to slightly modify the above process, such that users can start with an initial seed prompt (”I need a tool that goes to website X and gets all data for Y”), and then produces a more detailed structured prompt. This feels very much in line with the recent trend of “spec-driven development”.

So, overall this looks like this:

Reflecting a bit on the above, we can find that the core feature of such an approach lies in increased reusability reproducibility: When we use the final result, we actually execute code instead of running an agent that might make different decisions each term. Moreover, the final DML code can be verified in advance, maybe even with formal methods implmented in Prolog itself. Thinking evebn further, it isn’t hard to imagine an “agent reuse” functionality, where successful agent trajectories are compiled into static DML code.

On the other hand, we obviously lose a lot of the flexibility and adaptability that a pure agent-like approach (system prompt + set of tools + context engineering tricks) would provide. Nevertheless, I believe that for certain users and applications the DeepClause approach makes a lot more sense, especially in those situations where reproducibility and traceability are hard requirements.

Final remarks

This project was the first time that I went (almost) all-in with the latest generations of coding agents and I even though I was very sceptic in the beginning, I was deeply impressed by the power of these tools, especially with Claude 4.5 Sonnet and Opus. While I wrote the of the system (about 2000 lines of horrible Prolog-code) by myself, the usage of coding agents allowed me to very quickly iterate on ideas. Will these tools make profession obsolete? Probably not. Will it change the way we work? Yes. After the last 12 months, I do not think that there is any way around this.

So thanks to Sonnet and Opus DeepClause has reached a state where it is somewhat usable. In its current form it is implemented as a JavaScript runtime on top of the WASM version of SWI-Prolog. The runtime is exposed in a CLI, as well as an Electron app. Using the CLI or Electron app, users can manully create and run DML code, ask an agent to solve problems by automatically creating and running DML code, as well as create deployable bundles of DML code (=autogenerated APIs around a single piece of DML code). If you’re interested, please check ut the DeepClause Github Repo

Owing to the many different iterations made possible by Sonnet and Opus, DeepClause can sort of do everything and nothing at the same time, which I guess is the curse of most side projects, especially now that we’re in the vibe coding age.

Where will this project go in 2026? Honestly, I don’t know! There are plenty of ideas that are still left to try such as

Adding DMLs as skills into something like Claude Code

Build some framework for spec-driven-develoment on top of DML

Combining Prolog-style DCG grammars with LLMs

and probably many more...

Appendix: The DeepClause Meta Language

It is probably best to now introduce DML by example:

agent_main :-

yield("Hello World").

When DML code is executed, the runtime engine will try to find an “agent_main” rule and then pass it of to the meta-interpreter and execute it using “once” semantics, that is it will try to find exactly one solution for “agent_main” to be true (which might also involve backtracking) and then terminate. The “yield” predicate in the above example will pass back control to the runtime engine which will then simply output the argument passed to yield. Passing back and forth of control between runtime engine and interpreter is made possible using so called “Prolog engines”, which more or less behave like co-routines and have been part of SWI-Prolog for some time now.

So far, so good. But where do the LLMs come in? To answer that, let’s look at a more complete example. The following DML program performs a web search using an external tool, processes the results with a prompt, and presents the findings to the user.

agent_main :-

% Search the web

tool(web_search("latest AI breakthroughs 2024"), Results),

% Extract structured data using LLM

extract_breakthroughs(Results, Breakthroughs),

% Present findings

format_report(Breakthroughs, Report),

yield(Report).

% @-predicate: LLM-powered function

extract_breakthroughs(SearchResults, BreakthroughsList) :-

@("From the SearchResults, extract a list of major AI breakthroughs.

Each item should include: technology name, organization, and key innovation.

Return as a Prolog list of structured terms.").

% Standard Prolog predicate

format_report([], "No breakthroughs found.").

format_report([H|T], Report) :-

format_report(T, RestReport),

format(string(Report), "• ~w\n~w", [H, RestReport]).

Whenever the interpreter encounters a “tool” predicate, it will pass back control to the runtime engine, execute the tool (which can be implemented in whatever language the runtime engine is implemented in) and then passes results back to the interpreter, putting the raw search results in the Results variable. Running a prompt in DML is possible through so called @-predicates. These are always of the form “rule_head(Arg1, Arg2,...) :- @(String)”. During execution, control is again passed to the runtime, which proceeds to craft a special prompt that then returns Prolog terms of the form “rule_head(Arg1, Arg2,...)”. These terms are then substituted back into the interpreter, where execution continues. If an @-predicate returns more than one term, a choice point is created for each additional term. So if an @-predicate were designed such that it would return several possibilities to make it true, then these possibilities would be used in case the interpreter starts to backtrack. Similarly, if the LLM does not find a way to make the predicate true based on the arguments in rule_head, then a simple “this is false” signal will be passed back to the interpreter. In the above example, the entire “agent_main” predicate would then fail.

To make the program still produce something interesting or try some other ways of terminating, one can add more branches (= choice points) to the agent_main predicate. Thre resulting code will then look something like this:

agent_main :-

% Branch 1: Try Google Scholar for academic sources

tool(google_scholar_search("quantum computing", 10), Papers),

Papers \= "", % Verify we got results

analyze_papers(Papers, Analysis),

yield("Academic Analysis:\n\n{Analysis}").

agent_main :-

% Branch 2: Fallback to general web search

log("Scholar search failed, using web search"),

tool(web_search("quantum computing research"), Results),

summarize_findings(Results, Summary),

yield("Web Summary:\n\n{Summary}").

agent_main :-

% Branch 3: Last resort - provide general information

yield("I apologize, but I couldn't access current research.

However, I can explain quantum computing concepts if helpful.").

Advantages of a Meta-interpreter design

The decision to build DeepClause around a meta-interpreter was one of the most consequential design choices, offering significant advantages in security, verifiability, and auditability. A meta-interpreter is essentially an interpreter for a language written in that same language. While this concept might seem abstract, it provides a powerful layer of control and introspection that is often difficult to achieve in other architectures.

The primary security benefit comes from the meta-interpreter’s role as a controlled execution environment or sandbox. Before any goal or predicate is executed, the meta-interpreter can inspect it. This allows for the implementation of fine-grained security policies. For instance, it can maintain a whitelist of “safe” predicates, preventing the execution of potentially dangerous operations like arbitrary file deletion or unrestricted network access. By channeling all execution through this single point of control, the meta-interpreter ensures that the agent operates within predefined safety boundaries, mitigating risks associated with executing dynamically generated code.

Because the meta-interpreter processes each computational step explicitly, it can create a detailed audit trail of the entire execution. Every goal that is called, every rule that is tried, every success, failure, and backtracking point can be logged. This produces a complete, step-by-step trace of the agent’s reasoning process. This trace is invaluable for debugging and verification, as it makes the agent’s behavior transparent and auditable. Instead of a black box, you get a glass box, allowing you to understand precisely why the agent reached a certain conclusion or took a specific action.

The concept of a meta-interpreter is not exclusive to Prolog. One could, for example, write a Python interpreter in Python to gain similar benefits. However, Prolog’s nature makes it exceptionally well-suited for this task. Due to its homoiconicity—the principle that code can be represented as a data structure in the language itself—and its powerful pattern-matching capabilities, a basic Prolog meta-interpreter can be written with remarkable elegance and conciseness. Manipulating and inspecting code as data is a natural, first-class operation in Prolog, which dramatically simplifies the implementation compared to imperative languages. This makes Prolog an ideal foundation for building systems that are not only powerful but also secure and transparent by design.

Beyond Worflows: DML and Agents

This all sounds great, but what’s actually been achieved at this point? We have essentially replicated the core of LangChain/Langgraph inside a Prolog-like language, enabled by a meta-interpreter approach. Now, it is of course possible to use it to build something more complex, that is an actual agent in the current sense of the work. Clearly, we can go about two different ways of doing this:

Implement an agent loop in DML itself

Use any agent framework and build an agent that can generate, read, write and execute DML code.

Approach 1: Implementing an agent loop with DML

Feeding the documentation of DML into Gemini, we can ask it to create a ReAct style agent and it will happily comply and produce code that looks something like this:

% Branch 1: The primary ReAct agent loop

agent_main :-

param("task", "The task for the ReAct agent to solve.", Task),

( Task \= "" -> true ; (log(error="The 'task' parameter is missing."), fail) ),

log("Starting ReAct agent for task: '{Task}'."),

MaxIterations = 30,

InitialHistory = [],

InitialIteration = 1,

react_loop(Task, InitialHistory, InitialIteration, MaxIterations).

% Branch 2: Fallback if the loop fails (e.g., max iterations reached)

agent_main :-

param("task", "The task for the ReAct agent to solve.", Task),

log(error="The ReAct agent failed to complete the task '{Task}' within the allowed number of steps."),

end_thinking,

system("You are a helpful assistant explaining a failure."),

answer("I apologize, but I was unable to complete the task...").

% Recursive step: Think, Act, Observe, and loop

react_loop(Task, History, Iter, Max) :-

% 1. THINK: Generate the next thought and action based on the current state

format_history_for_prompt(History, FormattedHistory),

think(Task, FormattedHistory, Thought, Action),

log(Thought),

log("Action: {Action}"),

% 2. ACT: Check if the action is to finish or to use a tool

( Action = finish(FinalAnswer) ->

log("Task finished. Presenting final answer."),

end_thinking,

chat("What is the final answer? ...")

;

Action = tool_call(Tool),

log("Executing ~w", [Tool]),

execute_action(Action, Observation),

log("Observation: ~w", [Observation]),

% 3. OBSERVE & RECURSE: Add the new step to history and continue the loop

NewHistoryItem = step(Iter, Thought, Action, Observation),

append(History, [NewHistoryItem], NewHistory),

NextIter is Iter + 1,

react_loop(Task, NewHistory, NextIter, Max)

).

The think predicate itself is an @-predicate that contains the instructions for the LLM to reason about the task and decide on the next action.

think(Task, FormattedHistory, Thought, Action) :-

@("You are a large language model acting as the reasoning engine for a ReAct-style agent.

Your goal is to solve the user's task by breaking it down into a sequence of thoughts and actions.

**User's Task:**

{Task}

**Available Tools:**

{tools}

**Your Process:**

For each step, you must first think about the problem and your plan. Then, you must choose exactly ONE action to take.

The action can be either calling a tool or finishing the task.

**History of Previous Steps:**

{FormattedHistory}

**Your Turn:**

Based on the task and the history, decide on your next thought and action.

**Output Format:**

You must output a valid Prolog term in the format: `result(Thought, ActionTerm)`.

- `Thought` must be a string describing your reasoning (e.g., \"I need to find the current date, so I will use the linux vm.\").

- `ActionTerm` must be a Prolog terms of the following form:

- `tool_call(web_search(\"your search query\"))`

- `tool_call(linux_vm_with_sh_and_python(\"your shell command\"))`

- `finish(\"your final answer to the user\")`

Here, the tool_call predicate is defined as: tool_call(InToolTermWithToolarguments).

The Agent-Building Agent

Beyond the DML language itself, another key component of the DeepClause system is the agent that interprets natural language and orchestrates the DML execution. This “meta-agent,” defined in src/electron/main/dml-agent.js, is what a user interacts with in the DeepClause environment. Its primary purpose is not to solve tasks directly, but to manage DML files to solve tasks.

This agent operates on a ReAct-style loop, but its tools are introspective and focused on the DML ecosystem. Instead of tools for web search or file system access (which are delegated to the DML code itself), this agent has tools to manage the DML programs:

list_dml_files_tool: To see what DML programs are available.analyze_dml_file: To understand what a specific DML program does and what parameters it needs.read_dml_file: To inspect the source code of a DML program.run_dml_file_tool: To execute a DML program.create_dml_from_prompt: To generate a new DML program from a natural language description.save_last_dml: To persist a newly generated program.

The workflow is designed to be systematic: the agent first explores existing DML files to see if one can solve the user’s request. If not, it plans and generates a new DML file. This creates a feedback loop where the system can be extended with new capabilities simply by describing them in natural language. The agent effectively acts as a programmer, building and running small, specialized logic programs to achieve a larger goal.

This architecture also provides a clear path toward a form of episodic memory. When the agent successfully solves a novel problem by generating a new DML script, it can save that script using the save_last_dml tool. The saved DML file essentially becomes a memory of how to solve a particular type of problem—a learned skill. In subsequent interactions, the agent can discover these saved scripts, analyze them, and reuse them. This process of creating, saving, and later recalling DML programs allows the agent to build up a library of solutions over time, effectively learning from its experiences in a way that is both inspectable and durable.

References (incomplete, there are many more papers on Prolog <-> LLMs)

[1] Yang, X., et al. (2024). Arithmetic Reasoning with LLM: Prolog Generation & Permutation. arXiv. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.08222

[2] Triska, M. The Power of Prolog. Retrieved from https://www.metalevel.at/prolog

[3] Meijer, E. (2024). “Virtual Machinations: Using Large Language Models as Neural Computers.” ACM Queue, 22(1), 39-61. Available at: https://queue.acm.org/detail.cfm?id=3654921

[4] Meijer, E. (2025). “Unleashing the Power of End-User Programmable AI.” ACM Queue. (Note: As of late 2025, this article may still be forthcoming or recently published).

[5] Pan, L., et al. (2023). Logic-LM: Empowering Large Language Models with Symbolic Solvers for Faithful Logical Reasoning. arXiv. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.12295 (This paper is representative of the LoRP/Logic-LM approach).

[6] DeepClause Project Website. https://www.deepclause.ai